Reginald Gwynne Templer was a solicitor from Teignmouth, Devon, who became entangled in the infamous murder case of Emma Ann Whitehead Keyse in 1884. Miss Keyse, an elderly woman living in Babbacombe, was brutally murdered, and the primary suspect was her servant, John Henry George Lee, later known as “the man they could not hang.” Lee survived three botched execution attempts, and his case became one of the most famous in British criminal history.

Reginald Gwynne Templer was a solicitor from Teignmouth, Devon, who became entangled in the infamous murder case of Emma Ann Whitehead Keyse in 1884. Miss Keyse, an elderly woman living in Babbacombe, was brutally murdered, and the primary suspect was her servant, John Henry George Lee, later known as “the man they could not hang.” Lee survived three botched execution attempts, and his case became one of the most famous in British criminal history.

Templer’s connection to the case was complex. He was acquainted with Miss Keyse and had taken a particular interest in her cook, Elizabeth Harris, John Lee’s stepsister. His visits to “The Glen,” Keyse’s home, were not purely professional, as he was reportedly involved with Harris. Templer’s life took a tragic turn when he developed syphilis, which advanced to a stage known as “paralysis of the insane.”

This illness, common in the Victorian era, manifested in severe psychiatric symptoms, and by 1885, it had progressed to the point where Templer was unable to defend Lee effectively in court.

Some evidence suggests that Templer’s deteriorating mental health, which likely included fits of psychosis, may have contributed to the violent murder of Emma Keyse.

Templer himself died in 1886 at the age of 29, in a sanatorium. His death and burial were accompanied by rumours that his demise may have taken with him the secret of the Babbacombe murder.

Templer himself died in 1886 at the age of 29, in a sanatorium. His death and burial were accompanied by rumours that his demise may have taken with him the secret of the Babbacombe murder.

Reginald Gwynne Templer lived in Teignmouth. He was the eldest of six children born to Reginald William Templer and his wife Emily.

The Templer family built a church at the small village on the Stover estate Teigngrace where Reginald’s grandfather was Rector.

At the time of the Emma Keyse’ murder, the link between the Templer family and the Emma’s family was not known to outsiders. It has since been suggested that Reginald Gwynne Templer was in fact a confidante of Emma Keyse and a regular visitor at The Glen.

During the Victorian era the mere suggestion of a discreet liaison between a gentleman and a female servant (Elizabeth Harris – image: top right)) was out of the question but a blind eye was turned if such a relationship was not in the public domain. It is my long-held view that a relationship between Reginald Gwynne Templer and the cook, Elizabeth Harris did take place. At the time of the murder Elizabeth was pregnant (see the birth certificate).

The cover-up and false evidence that followed is quite remarkable. You only need to read the witness statements I have transcribed for this website.

Although dangerously ill with ‘Paralysis of the Insane’ the fact that Reginald Gwynne Templer was Lee’s defence lawyer is bizarre. A personal and long-term friend of the victim and her family is even more strange.

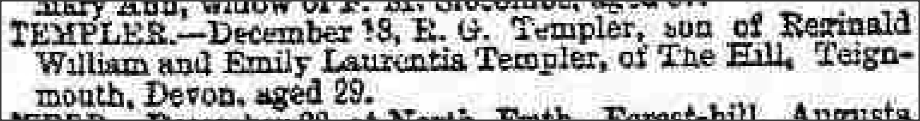

Reginald Gwynne Templer was admitted to the Holloway Sanatorium, an institution for the treatment of the insane, by his father, Reginald William Templer, on the 18th November 1886 and died there on December 18th 1886.

There are unconfirmed reports that he was shouting out extensively before he died. It’s alleged he was making references to Emma Keyse and her demise.

There are unconfirmed reports that he was shouting out extensively before he died. It’s alleged he was making references to Emma Keyse and her demise.

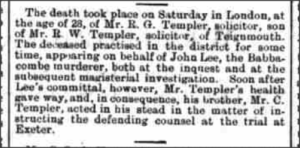

Although Reginald’s mental and physical condition was extremely poor it was be interesting to know what, if any, his references were. His death certificate clearly states the cause of death, ‘Paralysis of the Insane’. An announcement of his death was published in The London Daily News – Thursday 23 December 1886:

“The death took place on Saturday in London at the age of 28, of Mr R. G. Templer, solicitor, son of Mr R. W. Templer, solicitor, of Teignmouth. The deceased practised in the district for sometime, appearing on behalf of John Lee, the Babbacombe murderer, both at the inquest and the subsequent magisterial investigation. Soon after Lee’s committal, however, Mr Templer’s health gave way, and, in consequence, his brother, Mr C. Templer, acted in his stead in the matter of instructing the defending counsel at the trial at Exeter”.

The author of a 1936 newspaper article was the journalist Reg CowilI. He was convinced of the credentials of his informant and the authenticity of his story.

Although Cowill refers to ‘about the year 1890’, it is close enough to the date of Reginald Gwynne Templer’s funeral on 23rd December 1886. In 1975, the then editor of The Herald and Express, George Matthews, was questioned for the BBC’s documentary about the Babbacombe murder. His silence on screen is evidence enough that the man referred to in the article was (in my opinion) Reginald Gwynne Templer.

“About the year 1890 there stood at the side of an open grave, in a South Devon town, a well-known and local resident and his two sons. The man who had been buried was a public man of the town who had been very well-known, highly respected and very popular throughout South Devon. The young men were, also, in their turn, to become public men in the area. As they were moving away from the grave and the mourners were disbursing their father turned to them and said “we have buried this afternoon the secret of the Babbacombe murder.”

At the time they did not realise the significance of their father’s remark. It was nearly 20 years before they did, but long before that they were aware that their father knew a good many of the secrets of the dead man.

By an amazing coincidence John Lee himself gave them the explanation when he was released from prison.

Lee knew nothing of that funeral when the two young men stood at the open grave. He did not know that the brothers, to whom he went on his release, knew of the existence of a man who had been buried. All he knew was that he felt he had been suffering under the grave injustice for 22 years, he wanted to obtain the redress, and he had decided to talk the matter over with the two men — to have their advice as to what to do to get satisfaction.

The story he told them explained their father’s remark about the secret of the Babbacombe murder and their surprise as the facts were unfolded can be better imagined then described.

He started by declaring that he was not the Babbacombe murderer but that he knew who was, and that he had shielded him for over 20 years, only to discover, on his release from prison, that the murderer was dead.

The name of the murderer he gave. It was the name of the man at whose graveside the men on the opposite side of the table had stood (the full article is here).

Archive Nightmare:

Researching Reginald Gynne Templer is probably the most frustrating aspect of this work. Despite the lapse of 130 years, there are no descendants and no existing legal firms still operating Torquay who wish to discuss him, John Lee or the case. Some websites suggest he died anywhere except the actual location. Some suggest that he had nothing to do with or even knew Miss Keyse. The Holloway Sanitorium was, by Victorian standards, a ‘cutting edge’ entity. Detailed and precise records were kept of every aspect. Access to the archive is here. They say on their website:

“Some records are closed for a specific period to protect sensitive information (for example personal medical data). This may vary from 30 years to 100 years. These closure periods are not absolute but requests to gain access to such information need to be monitored and referred to the depositor for guidance”.

This would not apply to records relating to Reginald Gwynne Templer. Since the mid 1990’s I have endeavoured to access his archive following a tip-off that he was referring to the Babbacombe Murder on his deathbed. My most recent enquiry generates a standard reply from The Surrey Archive (despite the meticulous records produced at Holloways:

7 March 2012

Dear Mr Waugh

RECORDS RELATING TO REGINALD GWYNNE TEMPLER

Thank you for your e-mail of 4 March.

A search has been made in the records that we hold for Holloway Sanatorium. I looked at the earliest register that we hold, (the hospital opened in 1885), but unfortunately it did not contain an entry relating to Reginald Templer.

The Wellcome Library also holds some records of that period relating to Holloway Sanatorium. May I suggest that you contact them, to see if they are able to help you?

However, I must add that it is possible that the records no longer survive …

Further enquiries are currently ongoing to track and trace the elusive records. As for the wall of silence generated in Torquay and beyond – then this only generates more unfounded speculation and rumour which is not the basis of this work or any that I have been involved in. The Babbacombe Murder is an important part of Victorian British and Devonshire history. After 130 years little damage can be done by retrieving the facts and ‘putting the record straight’. Unfortunately there are some who don’t agree and prefer to create a rather silly and unprofessional veil of secrecy.

What is ‘General Paralysis of the Insane’?

“General paresis, also known as general paralysis of the insane or paralytic dementia, is a neuropsychiatric disorder affecting the brain and central nervous system, caused by syphilis infection. It was originally considered a psychiatric disorder when it was first scientifically identified around the nineteenth century, as the patient usually presented with psychotic symptoms of sudden and often dramatic onset. It is rare in most developed countries.

The diagnosis could be differentiated from other known psychoses by a characteristic abnormality in eye pupil reflexes (Argyll Robertson pupil), and, eventually, the development of muscular reflex abnormalities, seizures, memory impairment (dementia) and other signs of relatively pervasive neurocerebral deterioration.

Although there were recorded cases of remission of the symptoms, especially if they had not passed beyond the stage of psychosis, these individuals almost invariably suffered relapse within a few months to a few years. Otherwise, the patient was seldom able to return home because of the complexity, severity and unmanageability of the evolving symptom picture. Eventually, the patient would become completely incapacitated, bedfast, and die, the process taking about three to five years on average”.

In a letter to the Home Secretary during his imprisonment on 1 November 1887, John Lee wrote:

I wish to bring before your notice that the Solicitor that my parents employed to look after my case, was between the coroner’s inquest and the trial taken with a fit of insanity and all that I had told him about the case and all that he himself had prepared was of no use and just as the trial commenced his brother took the case into hand, but had nothing ready for my Counsel.

Reginald Gwynne Templer was buried in Teignmouth on 23 December 1886.

The Torbay Historian, Mike Holgate, in his first book about John Lee wrote:

“If Templer was guilty of the allegations made by Lee, there is little wonder that the balance of his mind was disturbed. Defending someone for a crime he himself had committed, facing prosecution witnesses recounting details of his horrendous crime, questioning the woman who was bearing his child: these factors must have placed an intolerable strain on his conscience”.

Even today the mere suggestion that Reginald Gwynne Templer was in fact Emma Keyse’ killer still creates controversy in certain quarters. Reg Cowill’s 1936 article (transcribed on this website) makes fascinating if explosive reading. It leaves a few questions unanswered.

On several occasions I tried to speak to and wrote to the law firm Hutchings & Hutchings (now Kitson Hutchings Solicitors) in Torquay who are connected to this case. Although a few generations on from the days of Thomas Hutchings, the first Chairman of Teignmouth Urban District Council and Ernest Hutchings who attended Reginald’s funeral, they still prefer not to reply to my letters and calls.

But the fact remains that with the vast cover-up, serious lack of actual evidence against Lee, it is a possibility that cannot be ruled out. And as time passes more archive is becoming available – it is my view that although Reginald Gwynne Templer has been dead more than 125 years, only time itself will tell if the archives finally expose the truth to the modern world.

Holloway Sanatorium, Egham, Surrey

Holloway Sanatorium was founded in 1885 by a wealthy entrepreneur, called Thomas Holloway, who had made an immense fortune through the sale of pills. He wished to bequeath his wealth to a suitable philanthropic cause and devised the idea of opening an asylum for the middle classes whose needs had hitherto been largely overlooked by county asylums which received large numbers of paupers and private establishments which took those rich enough to pay.

His aim was to build an asylum for ‘Persons of the reduced middle class who [would] pay a moderate income for their support’. It was to hold two hundred patients, of whom none were to be epileptic, paralysed or dirty. No patient was to remain there for more than a year, no hopeless cases were to be admitted, there was to be no readmission (although this rule seems to have been broken within a few years), and all patients were to come from the middle class. Unlike the bleak austerity of county asylums, which were often constructed and furnished more like prisons than hospitals, Holloway’s sanatorium was carefully planned to provide comfortable surroundings, exuberantly coloured and decorated in order to distract the attention of the patients from their mental afflictions. The Sanatorium closed in 1981 (source: Exploring Surrey’s Past).